Introduction

Welcome to the nearcore development guide!

The target audience of this guide are developers of nearcore itself. If you are a user of NEAR (either a contract developer, or validator running a node), please refer to the user docs at https://docs.near.org.

This guide is built with mdBook from sources in the nearcore repository. You can edit it by pressing the "edit" icon in the top right corner, we welcome all contributions. The guide is hosted at https://near.github.io/nearcore/.

The guide is organized as a collection of loosely coupled chapters -- you don't need to read them in order, feel free to peruse the TOC, and focus on the interesting bits. The chapters are classified into three parts:

- Architecture talks about how the code works. So, for example, if you are interested in how a transaction flows through the system, look there!

- Practices describe, broadly, how we write code. For example, if you want to learn about code style, issue tracking, or debugging performance problems, this is the chapter for you.

- Finally, the Misc part holds various assorted bits and pieces. We are trying to bias ourselves towards writing more docs, so, if you want to document something and it doesn't cleanly map to a category above, just put it in misc!

If you are unsure, start with the next chapter, Architecture Overview

Overview

This document describes the high-level architecture of nearcore. The focus here is on the implementation of the blockchain protocol, not the protocol itself. For reference documentation of the protocol, please refer to nomicon

Some parts of our architecture are also covered in this video series on YouTube.

Bird's Eye View

If we put the entirety of nearcore onto one picture, we get something like this:

Don't worry if this doesn't yet make a lot of sense: hopefully, by the end of this document the above picture would become much clearer!

Overall Operation

nearcore is a blockchain node -- it's a single binary (neard) which runs on

some machine and talks to other similar binaries running elsewhere. Together,

the nodes agree (using a distributed consensus algorithm) on a particular

sequence of transactions. Once transaction sequence is established, each node

applies transactions to the current state. Because transactions are fully

deterministic, each node in the network ends up with identical state. To allow

greater scalability, NEAR protocol uses sharding, which allows a node to hold

only a small subset (shard) of the whole state.

neard is a stateful, restartable process. When neard starts, the node

connects to the network and starts processing blocks (block is a batch of

transactions, processed together; transactions are batched into blocks for

greater efficiency). The results of processing are persisted in the database.

RocksDB is used for storage. Usually, the node's data is found in the ~/.near

directory. The node can be stopped at any moment and be restarted later. While

the node is offline it misses the block, so, after a restart, the sync process

kicks in which brings the node up-to-speed with the network by downloading the

missing bits of history from more up-to-date peer nodes.

Major components of nearcore:

-

JSON RPC. This HTTP RPC interface is how

neardcommunicates with non-blockchain outside world. For example, to submit a transaction, some client sends an RPC request with it to some node in the network. From that node, the transaction propagates through the network, until it is included in some block. Similarly, a client can send an HTTP request to a node to learn about current state of the blockchain. The JSON RPC interface is documented here. -

Network. If RPC is aimed "outside" the blockchain, "network" is how peer

neardnodes communicate with each other within blockchain. RPC carries requests from users of the blockchain, while network carries various messages needed to implement consensus. Two directly connected nodes communicate by sending protobuf-encoded messages over TCP. A node also includes logic to route messages for indirect peers through intermediaries. Oversimplifying a lot, it's enough for a new node to know an IP address of just one other network participant. From this bootstrap connection, the node learns how to communicate with any other node in the network. -

Client. Somewhat confusingly named, client is the logical state of the blockchain. After receiving and decoding a request, both RPC and network usually forward it in the parsed form to the client. Internally, client is split in two somewhat independent components: chain and runtime.

-

Chain. The job of chain, in a nutshell, is to determine a global order of transactions. Chain builds and maintains the blockchain data structure. This includes block and chunk production and processing, consensus, and validator selection. However, chain is not responsible for actually applying transactions and receipts.

-

Runtime. If chain selects the order of transactions, Runtime applies transaction to the state. Chain guarantees that everyone agrees on the order and content of transactions, and Runtime guarantees that each transaction is fully deterministic. It follows that everyone agrees on the "current state" of the blockchain. Some transactions are as simple as "transfer X tokens from Alice to Bob". But a much more powerful class of transactions is supported: "run this arbitrary WebAssembly code in the context of the current state of the chain". Running such "smart contract" transactions securely and efficiently is a major part of what runtime does. Today, runtime uses a JIT compiler to do that.

-

Storage. Storage is more of a cross-cutting concern, than an isolated component. Many parts of a node want to durably persist various bits of state to disk. One notable case is the logical state of the blockchain, and, in particular, data associated with each account. Logically, the state of account on a chain is a key-value map:

HashMap<Vec<u8>, Vec<u8>>. But there is a twist: it should be possible to provide a succinct proof that a particular key indeed holds a particular value. To allow that internally the state is implemented as a persistent (in both senses, "functional" and "on disk") merkle-patricia trie. -

Parameter Estimator. One kind of transaction we support is "run this arbitrary, Turing-complete computation". To protect from a

loop {}transaction halting the whole network, runtime implements resource limiting: each transaction runs with a certain finite amount of "gas", and each operation costs a certain amount of gas to perform. Parameter estimator is essentially a set of benchmark used to estimate relative gas costs of various operations.

Entry Points

neard/src/main.rs contains the main function that starts a blockchain node.

However, this file mostly only contains the logic to parse arguments and

dispatch different commands. start_with_config in nearcore/src/lib.rs is the

actual entry point and it starts all the actors.

JsonRpcHandler::process in the jsonrpc crate is the RPC entry point. It

implements the public API of a node, which is documented

here.

PeerManagerActor::spawn in the network is an entry for the other point of

contract with the outside world -- the peer-to-peer network.

Runtime::apply in the runtime crate is the entry point for transaction

processing logic. This is where state transitions actually happen, after chain

decided that, according to distributed consensus, which transitions need to

happen.

Code Map

This section contains some high-level overview of important crates and data structures.

core/primitives

This crate contains most of the types that are shared across different crates.

core/primitives-core

This crate contains types needed for runtime.

core/store/trie

This directory contains the MPT state implementation. Note that we usually use

TrieUpdate to interact with the state.

chain/chain

This crate contains most of the chain logic (consensus, block processing, etc).

ChainUpdate::process_block is where most of the block processing logic

happens.

Architecture Invariant: interface between chain and runtime is defined by

RuntimeAdapter. All invocations of runtime goes through RuntimeAdapter

State update

The blockchain state can be changed in the following two ways:

- Applying a chunk. This is how the state is normally updated: through

Runtime::apply. - State sync. State sync can happen in two cases:

- A node is far enough behind the most recent block and triggers state sync to fast forward to the state of a very recent block without having to apply blocks in the middle.

- A node is about to become validator for some shard in the next epoch, but it

does not yet have the state for that shard. In this case, it would run state

sync through the

catchuproutine.

chain/chunks

This crate contains most of the sharding logic which includes chunk creation,

distribution, and processing. ShardsManager is the main struct that

orchestrates everything here.

chain/client

This crate defines two important structs, Client and ViewClient. Client

includes everything necessary for the chain (without network and runtime) to

function and runs in a single thread. ViewClient is a "read-only" client that

answers queries without interfering with the operations of Client.

ViewClient runs in multiple threads.

chain/network

This crate contains the entire implementation of the p2p network used by NEAR blockchain nodes.

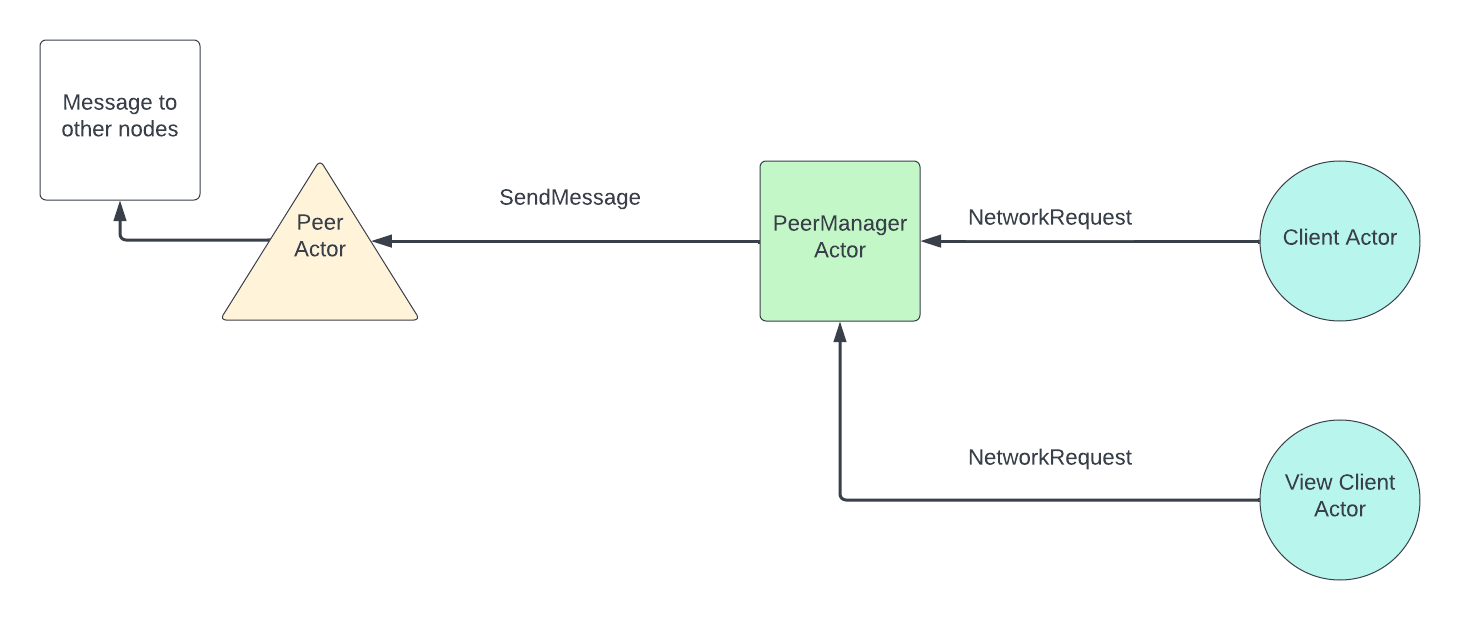

Two important structs here: PeerManagerActor and Peer. Peer manager

orchestrates all the communications from network to other components and from

other components to network. Peer is responsible for low-level network

communications from and to a given peer. Peer manager runs in one thread while

each Peer runs in its own thread.

Architecture Invariant: Network communicates to Client through

NetworkClientMessages and to ViewClient through NetworkViewClientMessages.

Conversely, Client and ViewClient communicates to network through

NetworkRequests.

chain/epoch_manager

This crate is responsible for determining validators and other epoch related information such as epoch id for each epoch.

Note: EpochManager is constructed in NightshadeRuntime rather than in

Chain, partially because we had this idea of making epoch manager a smart

contract.

chain/jsonrpc

This crate implements JSON-RPC API server to enable

submission of new transactions and inspection of the blockchain data, the

network state, and the node status. When a request is processed, it generates a

message to either ClientActor or ViewClientActor to interact with the

blockchain. For queries of blockchain data, such as block, chunk, account, etc,

the request usually generates a message to ViewClientActor. Transactions, on

the other hand, are sent to ClientActor for further processing.

runtime/runtime

This crate contains the main entry point to runtime -- Runtime::apply. This

function takes ApplyState, which contains necessary information passed from

chain to runtime, and a list of SignedTransaction and a list of Receipt, and

returns a ApplyResult, which includes state changes, execution outcomes, etc.

Architecture Invariant: The state update is only finalized at the end of

apply. During all intermediate steps state changes can be reverted.

runtime/near-vm-logic

VMLogic contains all the implementations of host functions and is the

interface between runtime and wasm. VMLogic is constructed when runtime

applies function call actions. In VMLogic, interaction with NEAR blockchain

happens in the following two ways:

VMContext, which contains lightweight information such as current block hash, current block height, epoch id, etc.External, which is a trait that contains functions to interact with blockchain by either reading some nontrivial data, or writing to the blockchain.

runtime/near-vm-runner

run function in runner.rs is the entry point to the vm runner. This function

essentially spins up the vm and executes some function in a contract. It

supports different wasm compilers including wasmer0, wasmer2, and wasmtime

through compile-time feature flags. Currently we use wasmer0 and wasmer2 in

production. The imports module exposes host functions defined in

near-vm-logic to WASM code. In other words, it defines the ABI of the

contracts on NEAR.

neard

As mentioned before, neard is the crate that contains that main entry points.

All the actors are spawned in start_with_config. It is also worth noting that

NightshadeRuntime is the struct that implements RuntimeAdapter.

core/store/src/db.rs

This file contains schema (DBCol) of our internal RocksDB storage - a good starting point when reading the code base.

Cross Cutting Concerns

Observability

The tracing crate is used for structured, hierarchical event output and logging. We also integrate Prometheus for light-weight metric output. See the style documentation for more information on the usage.

Testing

Rust has built-in support for writing unit tests by marking functions

with #[test] directive. Take full advantage of that! Testing not

only confirms that what was written works the way it was intended but

also help during refactoring since the caught unintended behaviour

changes.

Not all tests are created equal though and while some can need only

milliseconds to run, others may run for several seconds or even

minutes. Tests that take a long time should be marked as such with an

expensive_tests feature, for example:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { #[test] #[cfg_attr(not(feature = "expensive_tests"), ignore)] fn test_catchup_random_single_part_sync() { test_catchup_random_single_part_sync_common(false, false, 13) } }

Such tests will be ignored by default and can be executed by using

--ignored or --include-ignored flag as in cargo test -- --ignored or by compiling the tests with expensive_tests feature

enabled.

Because expensive tests are not run by default, they are also not run

in CI. Instead, they are run nightly and need to be explicitly

included in nightly/expensive.txt file; for example:

expensive --timeout=1800 near-client near_client tests::catching_up::test_catchup_random_single_part_sync

expensive --timeout=1800 near-client near_client tests::catching_up::test_catchup_random_single_part_sync --features nightly

For more details regarding nightly tests see nightly/README.md.

Note that what counts as a slow test isn’t exactly defined as of now. If it takes just a couple seconds than it’s probably fine. Anything slower should probably be classified as expensive test. In particular, if libtest complains the test takes more than 60 seconds than it definitely is.

How neard works

This chapter describes how neard works with a focus on implementation details and practical scenarios. To get a better understanding of how the protocol works, please refer to nomicon. For a high-level code map of nearcore, please refer to this document.

High level overview

On the high level, neard is a daemon that periodically receives messages from the network and sends messages to peers based on different triggers. Neard is implemented using an actor framework called actix.

Note: Using actix was decided in the early days of the implementation of nearcore and by no means represents our confidence in actix. On the contrary, we have noticed a number of issues with actix and are considering implementing an actor framework in house.

There are several important actors in neard:

-

PeerActorEach peer is represented by one peer actor and runs in a separate thread. It is responsible for sending messages to and receiving messages from a given peer. AfterPeerActorreceives a message, it will route it toClientActor,ViewClientActor, orPeerManagerActordepending on the type of the message. -

PeerManagerActorPeer Manager is responsible for receiving messages to send to the network from eitherClientActororViewClientActorand routing them to the rightPeerActorto send the bytes over the wire. It is also responsible to handle some types of network messages received and routed throughPeerActor. For the purpose of this document, we only need to know thatPeerManagerActorhandlesRoutedMessages. ForRoutedMessages, peer manager would decide whether they should be routed toClientActororViewClientActor. -

ClientActorClient actor is the “core” of neard. It contains all the main logic including consensus, block and chunk processing, state transition, garbage collection, etc. Client actor is single threaded. -

ViewClientActorView client actor can be thought of as a read-only interface to client. It only accesses data stored in a node’s storage and does not mutate any state. It is used for two purposes:- Answering rpc requests by fetching the relevant piece of data from storage

- Handle some network requests that do not require any changes to the storage, such as header sync, state sync, and block sync requests.

ViewClientActorruns in four threads by default but this number is configurable.

Data flow within neard

Flow for incoming messages:

Flow for outgoing messages:

How neard operates when it is fully synced

When a node is fully synced, the main logic of the node operates in the following way (the node is assumed to track all shards, as most nodes on mainnet do today):

- A block is produced by some block producer and sent to the node through broadcasting.

- The node receives a block and tries to process it. If the node is synced it presumably has the previous block and the state before the current block to apply. It then checks whether it has all the chunks available. If the node is not a validator node, it won’t have any chunk parts and therefore won’t have the chunks available. If the node is a validator node, it may already have chunk parts through chunk parts forwarding from other nodes and therefore may have already reconstructed some chunks. Anyways, if the node doesn’t have all chunks for all shards, it will request them from peers by parts.

- The chunk requests are sent and the node waits for enough chunk parts to be

received to reconstruct the chunks. For each chunk, 1/3 of all the parts

(100) is sufficient to reconstruct a chunk. In the meantime, if new blocks

arrive, they will be put into a

OrphanPool, waiting to be processed. If a chunk part request is not responded to withinchunk_request_retry_period, which is set to 400ms by default, then a request for the same chunk part would be sent again. - After all chunks are reconstructed, the node processes the current block by applying transactions and receipts from the chunks. Afterwards, it will update the head according to the fork choice rule, which only looks at block height. In other words, if the newly processed block is of higher height than the current head of the node, the head is updated.

- The node checks whether any blocks in the

OrphanPoolis ready to be processed in a BFS manner and processes all of them until none can be processed any more. Note that a block is put into theOrphanPoolif and only if its previous block is not accepted. - Upon acceptance of a block, the node would check whether it needs to run garbage collection. If it needs to, it would garbage collect two blocks worth of data at a time. The logic of garbage collection is complicated and could be found here.

- If the node is a validator node, it would start a timer after the current

block is accepted. After

min_block_production_delaywhich is currently configured to be 1.3s on mainnet, it would send an approval to the block producer of the next block (current block height + 1).

The main logic is illustrated below:

How neard works when it is synchronizing

PeerManagerActor periodically sends a NetworkInfo message to ClientActor

to update it on the latest peer information, which includes the height of each

peer. Once ClientActor realizes that it is more than sync_height_threshold

(which by default is set to 1) behind the highest height among peers, it starts

to sync. The synchronization process is done in three steps:

-

Header sync. The node first identifies the headers it needs to sync through a

get_locatorcalculation. This is essentially an exponential backoff computation that tries to identify commonly known headers between the node and its peers. Then it would request headers from different peers, at mostMAX_BLOCK_HEADER_HASHES(which is 512) headers at a time. -

After the headers are synced, the node would determine whether it needs to run state sync. The exact condition can be found here but basically a node would do state sync if it is more than 2 epochs behind the head of the network. State sync is a very complex process and warrants its own section. We will give a high level overview here.

- First, the node computes

sync_hashwhich is the hash of the block that identifies the state that the node wants to sync. This is guaranteed to be the first block of the most recent epoch. In fact, there is a check on the receiver side that this is indeed the case. The node would also request the block whose hash issync_hash - The node deletes basically all data (blocks, chunks, state) from its storage. This is not an optimal solution, but it makes the implementation for combining state easier when there is no stale data in storage.

- For the state of each shard that the node needs to download, it first requests a header that contains some metadata the node needs to know about. Then the node computes the number of state parts it needs to download and requests those parts from different peers who track the shard.

- After all parts are downloaded, the node combines those state parts and then finalizes the state sync by applying the last chunk included in or before the sync block so that the node has the state after applying sync block to be able to apply the next block.

- The node resets heads properly after state sync.

- First, the node computes

-

Block Sync. The node first gets the block with highest height that is on the canonical chain and request from there

MAX_BLOCK_REQUESTS(which is set to 5) blocks from different peers in a round robin order. The block sync routine runs again if head has changed (progress is made) or if a timeout (which is set to 2s) has happened.

Note: when a block is received and its height is no more than 500 + the node’s current head height, then the node would request its previous block automatically. This is called orphan sync and helps to speed up the syncing process. If, on the other hand, the height is more than 500 + the node’s current head height, the block is simply dropped.

How ClientActor works

ClientActor has some periodically running routines that are worth noting:

- Doomslug

timer.

This routine runs every

doosmslug_step_period(set to 100ms by default) and updates consensus information. If the node is a validator node, it also sends approvals when necessary. - Block

production.

This routine runs every

block_production_tracking_delay(which is set to 100ms by default) and checks if the node should produce a block. - Log summary. Prints a log line that summarizes block rate, average gas used, the height of the node, etc every 10 seconds.

- Resend chunk

requests.

This routine runs every

chunk_request_retry_period(which is set to 400ms). It resends the chunk part requests for those that are not yet responded to. - Sync.

This routine runs every

sync_step_period(which is set to 10ms by default) and checks whether the node needs to sync from its peers as well as actually starts the syncing process. - Catch

up.

This routine runs every

catchup_step_period(which is set to 100ms by default) and runs the catch up process. This only applies if a node validates shard A in epoch X and is going to validate a different shard B in epoch X+1. In this case, the node would start downloading the state for shard B at the beginning of epoch X. After the state downloading is complete, it would apply all blocks in the current epoch (epoch X) for shard B to ensure that the node has the state needed to validate shard B when epoch X+1 starts.

Garbage Collection

This document covers the basics of Chain garbage collection.

Currently we run garbage collection only in non-archival nodes, to keep the size of the storage under control. Therefore, we remove blocks, chunks and state that is ‘old’ enough - which in current configuration means 5 epochs ago.

We run a single ‘round’ of GC after a new block is accepted to the chain - and in order not to delay the chain too much, we make sure that each round removes at most 2 blocks from the chain.

How it works:

Imagine the following chain (with 2 forks)

In the pictures below, let’s assume that epoch length is 5 and we keep only 3 epochs (rather than 5 that is currently set in production) - otherwise the image becomes too large 😉

If head is in the middle of the epoch, the gc_stop will be set to the first block of epoch T-2, and tail & fork_tail will be sitting at the last block of epoch T-3.

(and no GC is happening in this round - as tail is next to gc_stop).

Next block was accepted on the chain (head jumped ahead), but still no GC happening in this round:

Now interesting things will start happening, once head ‘crosses’ over to the next epoch.

First, the gc_stop will jump to the beginning of the next epoch.

Then we’ll start the GC of the forks: by first moving the ‘fork_tail’ to match the gc_stop and going backwards from there.

It will start removing all the blocks that don’t have a successor (a.k.a the tip of the fork). And then it will proceed to lower height.

Will keep going until it ‘hits’ the tail.

In order not to do too much in one go, we’d only remove up to 2 block in each run (that happens after each head update).

Now, the forks are gone, so we can proceed with GCing of the blocks from canonical chain:

Same as before, we’d remove up to 2 blocks in each run:

Until we catchup to the gc_stop.

(the original drawings for this document are here: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1BiEuJqm4phwQbi-fjzHMZPzDL-94z9Dqkc3XPNnxKJM/edit?usp=sharing)

Trie

We use Merkle-Patricia Trie to store blockchain state. Trie is persistent, which means that insertion of new node actually leads to creation of new path to this node, and thus root of Trie after insertion will also be presented by new object.

Here we describe its implementation details which are closely related to Runtime.

Main structures

Trie

Trie stores the state - accounts, contract codes, access keys, etc. Each state item corresponds to the unique trie key. All types of trie keys are described in the TrieKey section. You can read more about this structure on Wikipedia.

Trie is stored in the RocksDB, which is persistent across node restarts. Trie

communicates with database using TrieStorage. On the database level, data is

stored in key-value format in DBCol::State column. There are two kinds of

records:

- trie nodes, for which key is constructed from shard id and

RawTrieNodeWithSizehash, and value is aRawTrieNodeWithSizeserialized by custom algorithm; - values (encoded contract codes, postponed receipts, etc.), for which key is constructed from shard id and hash of value, which maps to the encoded value.

So, value can be obtained from TrieKey as follows:

- start from the hash of

RawTrieNodeWithSizecorresponding to the root; - descend to the needed node using nibbles from

TrieKey; - extract underlying

RawTrieNode; - if it is a

LeaforBranch, it should contain hash of the value; - get value from storage by its hash and shard id.

Note that Trie is almost never called directly from Runtime, modifications

are made using TrieUpdate.

TrieUpdate

Provides a way to access storage and record changes to commit in the future. Update is prepared as follows:

- changes are made using

setandremovemethods, which are added toprospectivefield, - call

commitmethod which movesprospectivechanges tocommitted, - call

finalizemethod which preparesTrieChangesand state changes based oncommittedfield.

Note that finalize, Trie::insert and Trie::update do not update the

database storage. These functions only modify trie nodes in memory. Instead,

these functions prepares TrieChanges object, and Trie is actually updated

when ShardTries::apply_insertions is called, which puts new values to

DBCol::State part of key-value database.

TrieStorage

Stores all Trie nodes and allows to get serialized nodes by TrieKey hash

using retrieve_raw_bytes method.

There are three implementations of TrieStorage:

TrieCachingStorage- caches big values ever read byretrieve_raw_bytes.TrieRecordingStorage- records all key-value pairs ever read byretrieve_raw_bytes. Used for obtaining state parts (and challenges in the future).TrieMemoryPartialStorage- used for validating recorded partial storage.

Note that these storages use database keys, which are retrieved using hashes of

trie nodes using get_key_from_shard_id_and_hash method.

ShardTries

Contains stores and caches and allows to get Trie object for any shard.

Primitives

TrieKey

Describes all keys which may be inserted to Trie:

AccountContractCodeAccessKeyReceivedDataPostponedReceiptIdPendingDataCountPostponedReceiptDelayedReceiptIndicesDelayedReceiptContractData

Each key is uniquely converted to Vec<u8>. Internally, each such vector is

converted to NibbleSlice (nibble is a half of a byte), and each its item

corresponds to one step down in Trie.

TrieChanges

Stores result of updating Trie.

old_root: root before updatingTrie, i.e. inserting new nodes and deleting old ones,new_root: root after updatingTrie,insertions,deletions: vectors ofTrieRefcountChange, describing all inserted and deleted nodes.

TrieRefcountChange

Because we remove unused nodes during garbage collection, we need to track

reference count (rc) for each node. Another reason is that we can dedup

values. If the same contract is deployed 1000 times, we only store one contract

binary in storage and track its count.

This structure is used to update rc in the database:

trie_node_or_value_hash- hash of the trie node or value, used for uniting with shard id to get DB key,trie_node_or_value- serialized trie node or value,rc- change of reference count.

Note that for all reference-counted records, the actual value stored in DB is

the concatenation of trie_node_or_value and rc. The reference count is

updated using custom merge operation merge_refcounted_records.

This document describes how our network works. At this moment, it is known to be somewhat outdated, as we are in the process of refactoring the network protocol somewhat significantly.

1. Overview

Near Protocol uses its own implementation of a custom peer-to-peer network Peers who join network are represented by nodes and connections between them by edges.

The purpose of this document is to describe inner workings of near-network

package; and to be used as reference by future engineers to understand network

code without any prior knowledge.

2. Code structure

near-network runs on top of actor framework called Actix

(https://actix.rs/docs/). Code structure is split between 4 actors

PeerManagerActor, PeerActor, RoutingTableActor, EdgeValidatorActor

2.1 EdgeValidatorActor (currently called EdgeVerifierActor in the code (TODO rename))

EdgeValidatorActor runs on separate thread. The purpose of this actor is to

validate edges, where each edge represents a connection between two peers,

and it's signed with a cryptographic signature of both parties. The process of

edge validation involves verifying cryptographic signatures, which can be quite

expensive, and therefore was moved to another thread.

Responsibilities:

- validating edges by checking whenever cryptographic signatures match.

2.2 RoutingTableActor

RoutingTableActor maintain view of the P2P network represented by set of

nodes and edges.

In case a message needs to be sent between two nodes, that can be done directly

through Tcp connection. Otherwise, RoutingTableActor is responsible for ping

the best path between them.

Responsibilities:

- keep set of all edges of

P2P networkcalled routing table - connects to

EdgeValidatorActor, and asks for edges to be validated, when needed - has logic related to exchanging edges between peers

2.3 PeerActor

Whenever a new connection gets accepted, an instance of PeerActor gets

created. Each PeerActor keeps a physical a TCP connection to exactly one

peer.

Responsibilities:

- Maintaining physical connection.

- Reading messages from peers, decoding them, and then forwarding them to the right place.

- Encoding messages, sending them to peers on physical layer.

- Routing messages between

PeerManagerActorand other peers.

2.4 PeerManagerActor

PeerManagerActor is the main actor of near-network crate. It's acts as a

bridge connecting to the world outside, the other peers, and ClientActor and

ClientViewActor, which handle processing any operations on the chain.

PeerManagerActor maintains information about p2p network via (Routing Table

Actor), and indirectly, through PeerActor, connections to all some nodes on

the network. All messages going to other nodes, or coming from other nodes will

be routed through this Actor. PeerManagerActor is responsible for accepting

incoming connections from the outside world and creating PeerActors to manage

them.

Responsibilities:

- Accepting new connections

- Maintaining list of

PeerActors, creating, deleting them - Routing information about new edges between

PeerActorsandRoutingTableManager - Routing messages between

ViewClient,ViewClientActorandPeerActors, and consequently other peers. - Maintains

RouteBackstructure, which has information on how to send replies to messages

3. Code flow - initialization

PeerManagerActor actor gets started. PeerManagerActor open tcp server, which

listens to incoming connection. It starts RoutingTableActor, which then starts

EdgeValidatorActor. When connection incoming connection gets accepted, it

starts a new PeerActor on its own thread.

4. NetworkConfig

near-network reads configuration from NetworkConfig, which is a part client config.

Here is a list of features read from config

boot_nodes- list of nodes to connect to on startaddr- listening addressmax_num_peers- by default we connect up to 40 peers, current implementation supports upto 128 nodes.

5. Connecting to other peers.

Each peer maintains list of known peers. They are stored in the database. If

database is empty, the list of peers, called boot nodes, will be read from

boot_nodes option in config. Peer to connect to is chosen at random from list

of known nodes by PeerManagerActor::sample_random_peer method.

6. Edges & network - in code representation

P2P network is represented by list of peers, where each peer is

represented by structure PeerId, which is defined by peer's public key

PublicKey. And a list of edges, where each edge is represented by the

structure Edge.

Both are defined below.

6.1 PublicKey

We use two types of public keys:

- a 256 bit

ED25519public key - a 512 bit

Secp256K1public key

Public keys are defined in PublicKey enum, which consists of those two

variants.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct ED25519PublicKey(pub [u8; 32]); pub struct Secp256K1PublicKey([u8; 64]); pub enum PublicKey { ED25519(ED25519PublicKey), SECP256K1(Secp256K1PublicKey), } }

6.2 PeerId

Each peer is uniquely defined by its PublicKey, and represented by PeerId

struct.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct PeerId(PublicKey); }

6.3 Edge

Each edge is represented by Edge structure. It contains the following

- pair of nodes represented by their public keys.

nonce- a unique number representing state of an edge. Starting with 1. Odd number represents an active edge. Even number represent an edge in which one of nodes, confirmed that the edge is removed.- Signatures from both peers for active edges.

- Signature from one peers in case an edge got removed.

6.4 Graph representation

RoutingTableActor is responsible for storing and maintaining set of all edges.

They are kept in edge_info data structure of type HashSet<Edge>.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct RoutingTableActor { /// Collection of edges representing P2P network. /// It's indexed by `Edge::key()` key and can be search through by called `get()` function /// with `(PeerId, PeerId)` as argument. pub edges_info: HashSet<Edge>, /// ... } }

7. Code flow - connecting to a peer - handshake

When PeerManagerActor starts it starts to listen to a specific port.

7.1 - Step 1 - monitor_peers_trigger runs

PeerManager checks if we need to connect to another peer by running

PeerManager::is_outbound_bootstrap_needed method. If true we will try to

connect to new node. Let's call current node, node A.

7.2 - Step 2 - choosing node to connect to

Method PeerManager::sample_random_peer will be called, and it returns node B

that we will try to connect to.

7.3 - Step 3 - OutboundTcpConnect message

PeerManagerActor will send to itself a message OutboundTcpConnect in order

to connect to node B.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct OutboundTcpConnect { /// Peer information of the outbound connection pub target_peer_info: PeerInfo, } }

7.4 - Step 4 - OutboundTcpConnect message

On receiving the message handle_msg_outbound_tcp_connect method will be

called, which calls TcpStream::connect to create new connection.

7.5 - Step 5 - Connection gets established

Once connection with outgoing peer gets established. try_connect_peer method

will be called. And then new PeerActor will be created and started. Once

PeerActor starts it will send Handshake message to outgoing node B over

tcp connection.

This message contains protocol_version, node's A metadata, as well as all

information necessary to create Edge.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct Handshake { /// Current protocol version. pub(crate) protocol_version: u32, /// Oldest supported protocol version. pub(crate) oldest_supported_version: u32, /// Sender's peer id. pub(crate) sender_peer_id: PeerId, /// Receiver's peer id. pub(crate) target_peer_id: PeerId, /// Sender's listening addr. pub(crate) sender_listen_port: Option<u16>, /// Peer's chain information. pub(crate) sender_chain_info: PeerChainInfoV2, /// Represents new `edge`. Contains only `none` and `Signature` from the sender. pub(crate) partial_edge_info: PartialEdgeInfo, } }

7.6 - Step 6 - Handshake arrives at node B

Node B receives Handshake message. Then it performs various validation

checks. That includes:

- Check signature of edge from the other peer.

- Whenever,

nonceis the edge send matches. - Check whenever the protocol is above the minimum

OLDEST_BACKWARD_COMPATIBLE_PROTOCOL_VERSION - Other node

view of chainstate

If everything is successful, PeerActor will send RegisterPeer message to

PeerManagerActor. This message contains everything needed to add PeerActor

to list of active connections in PeerManagerActor.

Otherwise, PeerActor will be stopped immediately or after some timeout.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { pub struct RegisterPeer { pub(crate) actor: Addr<PeerActor>, pub(crate) peer_info: PeerInfo, pub(crate) peer_type: PeerType, pub(crate) chain_info: PeerChainInfoV2, // Edge information from this node. // If this is None it implies we are outbound connection, so we need to create our // EdgeInfo part and send it to the other peer. pub(crate) this_edge_info: Option<EdgeInfo>, // Edge information from other node. pub(crate) other_edge_info: EdgeInfo, // Protocol version of new peer. May be higher than ours. pub(crate) peer_protocol_version: ProtocolVersion, } }

7.7 - Step 7 - PeerManagerActor receives RegisterPeer message - node B

In handle_msg_consolidate method RegisterPeer message will be validated. If

successful register_peer method will be called, which adds PeerActor to list

of connected peers.

Each connected peer is represented in PeerActorManager in ActivePeer data

structure.

TODO: Rename ActivePeer to RegisterPeer.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Contains information relevant to an active peer. struct ActivePeer { // will be renamed to `ConnectedPeer` see #5428 addr: Addr<PeerActor>, full_peer_info: FullPeerInfo, /// Number of bytes we've received from the peer. received_bytes_per_sec: u64, /// Number of bytes we've sent to the peer. sent_bytes_per_sec: u64, /// Last time requested peers. last_time_peer_requested: Instant, /// Last time we received a message from this peer. last_time_received_message: Instant, /// Time where the connection was established. connection_established_time: Instant, /// Who started connection. Inbound (other) or Outbound (us). peer_type: PeerType, } }

7.8 - Step 8 - Exchange routing table part 1 - node B

At the end of register_peer method node B will performance

RoutingTableSync sync. Sending list of known edges representing full graph,

and list of known AnnounceAccount. Those will be covered later, in their

dedicated sections see sections TODO1, TODO2.

message: PeerMessage::RoutingTableSync(SyncData::edge(new_edge)),

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { /// Contains metadata used for routing messages to particular `PeerId` or `AccountId`. pub struct RoutingTableSync { // also known as `SyncData` (#5489) /// List of known edges from `RoutingTableActor::edges_info`. pub(crate) edges: Vec<Edge>, /// List of known `account_id` to `PeerId` mappings. /// Useful for `send_message_to_account` method, to route message to particular account. pub(crate) accounts: Vec<AnnounceAccount>, } }

7.9 - Step 9 - Exchange routing table part 2 - node A

Upon receiving RoutingTableSync message. Node A will reply with own

RoutingTableSync message.

7.10 - Step 10 - Exchange routing table part 2 - node B

Node B will get the message from A and update it's routing table.

8. Adding new edges to routing tables

This section covers the process of adding new edges, received from another nodes, to the routing table. It consists of several steps covered below.

8.1 Step 1

PeerManagerActor receives RoutingTableSync message containing list of new

edges to add. RoutingTableSync contains list of edges of the P2P network.

This message is then forwarded to RoutingTableActor.

8.2 Step 2

PeerManagerActor forwards those edges to RoutingTableActor inside of

ValidateEdgeList struct.

ValidateEdgeList contains:

- list of edges to verify

- peer who send us the edges

8.3 Step 3

RoutingTableActor gets the ValidateEdgeList message. Filters out edges

that have already been verified, those that are already in

RoutingTableActor::edges_info.

Then, it updates edge_verifier_requests_in_progress to mark that edge

verifications are in progress, and edges shouldn't be pruned from Routing Table

(see section TODO).

Then, after removing already validated edges, the modified message is forwarded

to EdgeValidatorActor.

8.4 Step 4

EdgeValidatorActor goes through list of all edges. It checks whether all edges

are valid (their cryptographic signatures match, etc.).

If any edge is not valid peer will be banned.

Edges that are validated are written to a concurrent queue

ValidateEdgeList::sender. This queue is used to transfer edges from

EdgeValidatorActor, back to PeerManagerActor.

8.5 Step 5

broadcast_validated_edges_trigger runs, and gets validated edges from

EdgeVerifierActor.

Every new edge will be broadcast to all connected peers.

And then, all validated edges received from EdgeVerifierActor will be sent

again to RoutingTableActor inside AddVerifiedEdges.

8.5 Step 6

When RoutingTableActor receives RoutingTableMessages::AddVerifiedEdges, the

methodadd_verified_edges_to_routing_table will be called. It will add edges to

RoutingTableActor::edges_info struct, and mark routing table, that it needs

recalculation see RoutingTableActor::needs_routing_table_recalculation.

9 Routing table computation

Routing table computation does a few things:

- For each peer

B, calculates set of peers|C_b|, such that each peer is on the shortest path toB. - Removing unreachable edges from memory and storing them to disk.

- The distance is calculated as the minimum number of nodes on the path from

given node

A, to each other node on the network. That is,Ahas a distance of0to itself. It's neighbors will have a distance of1. The neighbors of theirs neighbors will have a distance of2, etc.

9.1 Step 1

PeerManagerActor runs a update_routing_table_trigger every

UPDATE_ROUTING_TABLE_INTERVAL seconds.

RoutingTableMessages::RoutingTableUpdate message is sent to

RoutingTableActor to request routing table re-computation.

9.2 Step 2

RoutingTableActor receives the message, and then

- calls

recalculate_routing_tablemethod, which computesRoutingTableActor::peer_forwarding: HashMap<PeerId, Vec<PeerId>>. For eachPeerIdon the network, gives list of connected peers, which are on the shortest path to the destination. It marks reachable peers inpeer_last_time_reachablestruct. - calls

prune_edgeswhich removes from memory all edges, that were not reachable for at least 1 hour, based onpeer_last_time_reachabledata structure. Those edges are then stored to disk.

9.3 Step 3

RoutingTableActor sends RoutingTableUpdateResponse message back to

PeerManagerActor.

PeerManagerActor keep local copy of edges_info, called local_edges_info

containing only edges adjacent to current node.

RoutingTableUpdateResponsecontains list of local edges, whichPeerManagerActorshould remove.peer_forwardingwhich represent on how to route messages in the P2P networkpeers_to_ban- list of peers to ban for sending us edges, which failed validation inEdgeVerifierActor.

9.4 Step 4

PeerManagerActor received RoutingTableUpdateResponse and then:

- updates local copy of

peer_forwarding, used for routing messages. - removes

local_edges_to_removefromlocal_edges_info. - bans peers, who sent us invalid edges.

10. Message transportation layers.

This section describes different protocols of sending messages currently used in

Near

10.1 Messages between Actors.

Near is build on Actix's actor framework.

(https://actix.rs/book/actix/sec-2-actor.html) Usually each actor runs on its

own dedicated thread. Some, like PeerActor have one thread per each instance.

Only messages implementing actix::Message, can be sent using between threads.

Each actor has its own queue; Processing of messages happens asynchronously.

We should not leak implementation details into the spec.

Actix messages can be found by looking for impl actix::Message.

10.2 Messages sent through TCP

Near is using borsh serialization to exchange messages between nodes (See

https://borsh.io/). We should be careful when making changes to them. We have to

maintain backward compatibility. Only messages implementing BorshSerialize,

BorshDeserialize can be sent. We also use borsh for database storage.

10.3 Messages sent/received through chain/jsonrpc

Near runs a json REST server. (See actix_web::HttpServer). All messages sent

and received must implement serde::Serialize and serde::Deserialize.

11. Code flow - routing a message

This is the example of the message that is being sent between nodes

(RawRoutedMessage)

(https://github.com/near/nearcore/blob/fa8749dc60fe0de8e94c3046571731c622326e9f/chain/network-primitives/src/types.rs#L362)

Each of these methods have a target - that is either the account_id or peer_id

or hash (which seems to be used only for route back...). If target is the

account - it will be converted using routing_table.account_owner to the peer.

Upon receiving the message, the PeerManagerActor will sign it

(https://github.com/near/nearcore/blob/master/chain/network/src/peer_manager.rs#L1285)

And convert into RoutedMessage (which also have things like TTL etc.).

Then it will use the routing_table, to find the route to the target peer (add

route_back if needed) and then send the message over the network as

PeerMessage::Routed. Details about routing table computations are covered in

section 8.

When Peer receives this message (as PeerMessage::Routed), it will pass it to

PeerManager (as RoutedMessageFrom), which would then check if the message is

for the current PeerActor. (if yes, it would pass it for the client) and if

not - it would pass it along the network.

All these messages are handled by receive_client_message in Peer.

(NetworkClientMessags) - and transferred to ClientActor in

(chain/client/src/client_actor.rs)

NetworkRequests to PeerManager actor trigger the RawRoutedMessage for

messages that are meant to be sent to another peer.

lib.rs (ShardsManager) has a network_adapter - coming from client’s

network_adapter that comes from ClientActor that comes from start_client call

that comes from start_with_config (that crates PeerManagerActor - that is

passed as target to network_recipent).

12. Database

12.1 Storage of deleted edges

Everytime a group of peers becomes unreachable at the same time; We store edges belonging to them in components. We remove all of those edges from memory, and save them to database, If any of them were to be reachable again, we would re-add them. This is useful in case there is a network split, to recover edges if needed.

Each component is assigned a unique nonce, where first one is assigned nonce

0. Each new component, a get assigned a consecutive integer.

To store components, we have the following columns in the DB.

DBCol::LastComponentNonceStorescomponent_nonce: u64, which is the last used nonce.DBCol::ComponentEdgesMapping fromcomponent_nonceto list of edges.DBCol::PeerComponentMapping frompeer_idto last componentnonceit belongs to.

12.2 Storage of account_id to peer_id mapping

ColAccountAnouncements -> Stores a mapping from account_id to tuple

(account_id, peer_id, epoch_id, signature).

Overview

This chapter describes various development processes and best practices employed at nearcore.

Code Style

This document specifies the code style to use in the nearcore repository. The primary goal here is to achieve consistency, maintain it over time, and cut down on the mental overhead related to style choices.

Right now, nearcore codebase is not perfectly consistent, and the style

acknowledges this. It guides newly written code and serves as a tie breaker for

decisions. Rewriting existing code to conform 100% to the style is not a goal.

Local consistency is more important: if new code is added to a specific file,

it's more important to be consistent with the file rather than with this style

guide.

This is a live document, which intentionally starts in a minimal case. When doing code-reviews, consider if some recurring advice you give could be moved into this document.

Formatting

Use rustfmt for minor code formatting decisions. This rule is enforced by CI

Rationale: rustfmt style is almost always good enough, even if not always

perfect. The amount of bikeshedding saved by rustfmt far outweighs any

imperfections.

Idiomatic Rust

While the most important thing is to solve the problem at hand, we strive to

implement the solution in idiomatic Rust, if possible. To learn what is

considered idiomatic Rust, a good start are the Rust API guidelines (but keep in

mind that nearcore is not a library with public API, not all advice applies

literally):

https://rust-lang.github.io/api-guidelines/about.html

When in doubt, ask question in the Rust 🦀 Zulip stream or during code review.

Rationale: Consistency, as there's usually only one idiomatic solution amidst many non-idiomatic ones. Predictability, you can use the APIs without consulting documentation. Performance, ergonomics and correctness: language idioms usually reflect learned truths, which might not be immediately obvious.

Style

This section documents all micro-rules which are not otherwise enforced by

rustfmt.

Avoid AsRef::as_ref

When you have some concrete type, prefer .as_str, .as_bytes, .as_path over

generic .as_ref. Only use .as_ref when the type in question is a generic

T: AsRef<U>.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // GOOD fn log_validator(account_id: AccountId) { metric_for(account_id.as_str()) .increment() } // BAD fn log_validator(account_id: AccountId) { metric_for(account_id.as_ref()) .increment() } }

Note that Option::as_ref, Result::as_ref are great, use do use them!

Rationale: readability and churn-resistance. There might be more than one

AsRef<U> implementation for a given type (with different Us). If a new

implementation is added, some of the .as_ref() calls might break. See also

https://github.com/rust-lang/rust/issues/62586.

Avoid references to Copy-types

Various generic APIs in Rust often return references to data (&T). When T is

a small Copy type like i32, you end up with &i32 while many API expect

i32, so dereference has to happen somewhere. Prefer dereferencing as early

as possible, typically in a pattern:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // GOOD fn compute(map: HashMap<&'str, i32>) { if let Some(&value) = map.get("key") { process(value) } } fn process(value: i32) { ... } // BAD fn compute(map: HashMap<&'str, i32>) { if let Some(value) = map.get("key") { process(*value) } } fn process(value: i32) { ... } }

Rationale: if the value is used multiple times, dereferencing in the pattern saves keystrokes. If the value is used exactly once, we just want to be consistent. Additional benefit of early deref is reduced scope of borrow.

Note that for some big Copy types, notably CryptoHash, we sometimes use

references for performance reasons. As a rule of thumb, T is considered big if

size_of::<T>() > 2 * size_of::<usize>().

Prefer for loops over for_each and try_for_each methods

Iterators offer for_each and try_for_each methods which allow executing

a closure over all items of the iterator. This is similar to using a for loop

but comes with various complications and may lead to less readable code. Prefer

using a loop rather than those methods, for example:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // GOOD for outcome_with_id in result? { *total_gas_burnt = safe_add_gas(*total_gas_burnt, outcome_with_id.outcome.gas_burnt)?; outcomes.push(outcome_with_id); } // BAD result?.into_iter().try_for_each( |outcome_with_id: ExecutionOutcomeWithId| -> Result<(), RuntimeError> { *total_gas_burnt = safe_add_gas(*total_gas_burnt, outcome_with_id.outcome.gas_burnt)?; outcomes.push(outcome_with_id); Ok(()) }, )?; }

Rationale: The for_each and try_for_each method don’t play nice with

break and continue statements nor do they mesh well with async IO (since

.await inside of the closure isn’t possible). And while try_for_each allows

for the use of question mark operator, one may end up having to uses it twice:

once inside the closure and second time outside the call to try_for_each.

Furthermore, usage of the functions often introduce some minor syntax noise.

There are situations when those methods may lead to more readable code. Common example are long call chains. Even then such code may evolve with the closure growing and leading to less readable code. If advantages of using the methods aren’t clear cut, it’s usually better to err on side of more imperative style.

Lastly, anecdotally the methods (e.g. when used with chain or flat_map) may

lead to faster code. This intuitively makes sense but it’s worth to keep in

mind that compilers are pretty good at optimising and in practice may generate

optimal code anyway. Furthermore, optimising code for readability may be more

important (especially outside of hot path) than small performance gains.

Prefer to_string to format!("{}")

Prefer calling to_string method on an object rather than passing it through

format!("{}") if all you’re doing is converting it to a String.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // GOOD lat hash = block_hash.to_string(); let msg = format!("{}: failed to open", path.display()); // BAD lat hash = format!("{block_hash}"); let msg = path.display() + ": failed to open"; }

Rationale: to_string is shorter to type and also faster.

Import Granularity

Group import by module, but not deeper:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // GOOD use std::collections::{hash_map, BTreeSet}; use std::sync::Arc; // BAD - nested groups. use std::{ collections::{hash_map, BTreeSet}, sync::Arc, }; // BAD - not grouped together. use std::collections::BTreeSet; use std::collections::hash_map; use std::sync::Arc; }

This corresponds to "rust-analyzer.assist.importGranularity": "module" setting

in rust-analyzer

(docs).

Rationale: Consistency, matches existing practice.

Import Blocks

Do not separate imports into groups with blank lines. Write a single block of

imports and rely on rustfmt to sort them.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // GOOD use crate::types::KnownPeerState; use borsh::BorshSerialize; use near_primitives::utils::to_timestamp; use near_store::{DBCol::Peers, Store}; use rand::seq::SliceRandom; use std::collections::HashMap; use std::net::SocketAddr; // BAD -- several groups of imports use std::collections::HashMap; use std::net::SocketAddr; use borsh::BorshSerialize; use rand::seq::SliceRandom; use near_primitives::utils::to_timestamp; use near_store::{DBCol::Peers, Store}; use crate::types::KnownPeerState; }

Rationale: Consistency, ease of automatic enforcement. Today stable rustfmt can't split imports into groups automatically, and doing that manually consistently is a chore.

Derives

When deriving an implementation of a trait, specify a full path to the traits provided by the external libraries:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // GOOD #[derive(Copy, Clone, serde::Serialize, thiserror::Error, strum::Display)] struct Grapefruit; // BAD use serde::Serialize; use thiserror::Error; use strum::Display; #[derive(Copy, Clone, Serialize, Error, Display)] struct Banana; }

As an exception to this rule, it is okay to use either style when the derived trait already

includes the name of the library (as would be the case for borsh::BorshSerialize.)

Rationale: Specifying a full path to the externally provided derivations here makes it

straightforward to differentiate between the built-in derivations and those provided by the

external crates. The surprise factor for derivations sharing a name with the standard

library traits (Display) is reduced and it also acts as natural mechanism to tell apart names

prone to collision (Serialize), all without needing to look up the list of imports.

Standard Naming

- Use

-rather than_in crate names and in corresponding folder names. - Avoid single-letter variable names especially in long functions. Common

i,jetc. loop variables are somewhat of an exception but since Rust encourages use of iterators those cases aren’t that common anyway. - Follow standard Rust naming patterns such as:

- Don’t use

get_prefix for getter methods. A getter method is one which returns (reference to) a field of an object. - Use

set_prefix for setter methods. An exception are builder objects which may use different naming style. - Use

into_prefix for methods which consumeselfandto_prefix for methods which don’t.

- Don’t use

- Use

get_block_headerrather thanget_headerfor methods which return a block header. - Don’t use

_by_hashsuffix for methods which lookup chain objects (blocks, chunks, block headers etc.) by their hash (i.e. their primary identifier). - Use

_by_heightand similar suffixes for methods which lookup chain objects (blocks, chunks, block headers etc.) by their height or other property which is not their hash.

Rationale: Consistency.

Documentation

When writing documentation in .md files, wrap lines at approximately 80

columns.

<!-- GOOD -->

Manually reflowing paragraphs is tedious. Luckily, most editors have this

functionality built in or available via extensions. For example, in Emacs you

can use `fill-paragraph` (<kbd>M-q</kbd>), (neo)vim allows rewrapping with `gq`,

and VS Code has `stkb.rewrap` extension.

<!-- BAD -->

One sentence per-line is also occasionally used for technical writing.

We avoid that format though.

While convenient for editing, it may be poorly legible in unrendered form

<!-- BAD -->

Definitely don't use soft-wrapping. While markdown mostly ignores source level line breaks, relying on soft wrap makes the source completely unreadable, especially on modern wide displays.

Tracing

When emitting events and spans with tracing prefer adding variable data via

tracing's field mechanism.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // GOOD debug!( target: "client", validator_id = self.client.validator_signer.as_ref().map(|vs| { tracing::field::display(vs.validator_id()) }), %hash, "block.previous_hash" = %block.header().prev_hash(), "block.height" = block.header().height(), %peer_id, was_requested "Received block", ); }

Most apparent violation of this rule will be when the event message utilizes any form of formatting, as seen in the following example:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // BAD debug!( target: "client", "{:?} Received block {} <- {} at {} from {}, requested: {}", self.client.validator_signer.as_ref().map(|vs| vs.validator_id()), hash, block.header().prev_hash(), block.header().height(), peer_id, was_requested ); }

Always specify the target explicitly. A good default value to use is the crate

name, or the module path (e.g. chain::client) so that events and spans common

to a topic can be grouped together. This grouping can later be used for

customizing of which events to output.

Rationale: This makes the events structured – one of the major value propositions of the tracing ecosystem. Structured events allow for immediately actionable data without additional post-processing, especially when using some of the more advanced tracing subscribers. Of particular interest would be those that output events as JSON, or those that publish data to distributed event collection systems such as opentelemetry. Maintaining this rule will also usually result in faster execution (when logs at the relevant level are enabled.)

Spans

Use the spans to introduce context and grouping to and between events instead of manually adding such information as part of the events themselves. Most of the subscribers ingesting spans also provide a built-in timing facility, so prefer using spans for measuring the amount of time a section of code needs to execute.

Give spans simple names that make them both easy to trace back to code, and to

find a particular span in logs or other tools ingesting the span data. If a

span begins at the top of a function, prefer giving it a name of that function,

otherwise prefer a snake_case name.

Use the regular span API over convenience macros such as #[instrument], as

this allows instrumenting portions of a function without affecting the code

structure:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn compile_and_serialize_wasmer(code: &[u8]) -> Result<wasmer::Module> { let _span = tracing::debug_span!(target: "vm", "compile_and_serialize_wasmer").entered(); // ... // _span will be dropped when this scope ends, terminating the span created above. // You can also `drop` it manually, to end the span early with `drop(_span)`. } }

Rationale: Much as with events, this makes the information provided by spans

structured and contextual. This information can then be output to tooling in an

industry standard format, and can be interpreted by an extensive ecosystem of

tracing subscribers.

Event and span levels

The INFO level is enabled by default, use it for information useful for node

operators. The DEBUG level is enabled on the canary nodes, use it for

information useful in debugging testnet failures. The TRACE level is not

generally enabled, use it for arbitrary debug output.

Metrics

Consider adding metrics to new functionality. For example, how often each type of error was triggered, how often each message type was processed.

Rationale: Metrics are cheap to increment, and they often provide a significant insight into operation of the code, almost as much as logging. But unlike logging metrics don't incur a significant runtime cost.

Naming

Prefix all nearcore metrics with near_.

Follow [https://prometheus.io/docs/practices/naming/](Prometheus naming convention)

for new metrics.

Rationale: The near_ prefix makes it trivial to separate metrics exported

by nearcore from other metrics, such as metrics about the state of the machine

that runs neard.

Performance

In most cases incrementing a metric is cheap enough never to give it a second thought. However accessing a metric with labels on a hot path needs to be done carefully.

If a label is based on an integer, use a faster way of converting an integer

to the label, such as the itoa crate.

For hot code paths, re-use results of with_label_values() as much as possible.

Rationale: We've encountered issues caused by the runtime costs of incrementing metrics before. Avoid runtime costs of incrementing metrics too often.

Tracking issues

nearcore uses so called "tracking issues" to coordinate larger pieces of work

(e.g. implementation of new NEPs). Such issues are tagged with the

C-tracking-issue

label.

The goal of tracking issues is to serve as a coordination point. They can help new contributors and other interested parties come up-to-speed with the current state of projects. As such, they should link to things like design docs, todo-lists of sub-issues, existing implementation PRs, etc.

One can further use tracking issues to:

- get a feeling for what's happening in

nearcoreby looking at the set of open tracking issues. - find larger efforts to contribute to as tracking issues usually contain up-for-grabs todo lists.

- follow progress of a specific features by subscribing to the issue on Github.

If you are leading or participating in a larger effort, please create a tracking issue for your work.

Guidelines

- Tracking issues should be maintained in the

nearcorerepository. If the projects are security sensitive, then they should be maintained in thenearcore-privaterepository. - The issues should be kept up-to-date. At a minimum, all new context should be added as comments, but preferably the original description should be edited to reflect the current status.

- The issues should contain links to all the relevant design documents which should also be kept up-to-date.

- The issues should link to any relevant NEP if applicable.

- The issues should contain a list of todo tasks which should be kept up-to-date as new work items are discovered and other items are done. This helps others gauge progress and helps lower the barrier of entry for others to participate.

- The issues should contain links to relevant Zulip discussions. Prefer open forums like Zulip for discussions. When necessary, closed forums like video calls can also be used but care should be taken to document a summary of the discussions.

- For security sensitive discussions, use the appropriate private Zulip streams.

This issue is a good example of how tracking issues should be maintained.

Background

The idea of tracking issues is also used to track project work in the Rust language. See this post for a rough description and these issues for how they are used in Rust.

Fast Builds

nearcore is implemented in Rust and is a fairly sizable project, so it takes a while to build. This chapter collects various tips to make the process faster.

Optimizing build times is a bit of a black art, so please do benchmarks on your machine to verify that the improvement work for you. Changing some configuration and making some type, which prevents it from improving build times is an extremely common failure mode!

Rust Perf Book contains a section on compilation time as well!

Release Builds and Link Time Optimization

Obviously, cargo build --release is slower than cargo build. What's not

entirely obvious is that cargo build -r is not as slow as it could be: our

--release profile is somewhat optimized for fast builds, as it doesn't enable

full LTO.

When building production binaries, we use lto=true and codegen-units=1

options, which make the build significantly slower (but the resulting binary

somewhat faster). Keep this in mind when running benchmarks or parameter

estimation.

Linker

By default, rustc uses system's linker, which might be quite slow. Using lld

(LLVM linker) or mold (very new, very fast linker) is usually a big win.

I don't know what's the official source of truth for using alternative linkers, I usually refer to this comment.

Usually, adding

[build]

rustflags = ["-C", "link-arg=-fuse-ld=lld"]

to ~/.cargo/config is the most convenient approach.

lld itself can be installed with sudo apt install lld.

Prebuilt RocksDB

By default, we compile RocksDB (a C++ project) from source, which takes a lot of

time. A faster alternative is to link to a prebuilt copy of RocksDB. This is a

huge win, especially if you clean ./target directory frequently.

To use prebuilt RocksDB set ROCKSDB_LIB_DIR environment variable to location

where librocksdb.a file is installed:

$ export ROCKSDB_LIB_DIR=/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu

$ cargo build -p neard

Note that the system must provide a recent version of the library which,

depending on operating system you’re using, may require installing packages from

testing branches. For example, on Debian it requires installing

librocksdb-dev from experimental version:

echo 'deb http://ftp.debian.org/debian experimental main contrib non-free' |

sudo tee -a /etc/apt/sources.list

sudo apt update

sudo apt -t experimental install librocksdb-dev

ROCKSDB_LIB_DIR=/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu

export ROCKSDB_LIB_DIR

Global Compilation Cache

By default, Rust uses incremental compilation, with intermediate artifacts

stored in the project-local ./target directory.

sccache utility can be used to add a

global compilation to the mix:

$ cargo install sccache

$ export RUSTC_WRAPPER="sccache"

$ export SCCACHE_CACHE_SIZE="30G"

$ cargo build -p neard

sccache intercepts calls to rustc and pattern-matches compiler's command

line to get a cached result.

IDEs Are Bad For Environment

Generally, the knobs in this section are controlled either via global

configuration in ~/.cargo/config or environmental variables.

Environmental variables are notoriously easy to lose, especially if you are working both from a command line and from a graphical IDE. Double check that you are not missing any of our build optimizations, the failure mode here is nasty, as the stuff just takes longer to compile without givin any visual indication of an error.

direnv sometimes can be used to conveniently manage

project-specific environmentalvariable.

General principles

- Every PR needs to have test coverage in place. Sending the code change and deferring tests for a future change is not acceptable.

- Tests need to either be sufficiently simple to follow, or have good documentation to explain why certain actions are made and conditions are expected.

- When implementing a PR, make sure to run the new tests with the change disabled and confirm that they fail! It is extremely common to have tests that pass without the change that is being tested.

- The general rule of thumb for a reviewer is to first review the tests, and ensure that they can convince themselves that the code change that passes the tests must be correct. Only then the code should be reviewed.

- Have the assertions in the tests as specific as possible. For example, do not

do

assert!(result.is_err()), expect the specific error instead.

Tests hierarchy

In NEAR Reference Client we largely split tests into three categories:

- Relatively cheap sanity or fast fuzz tests. It includes all the

#[test]Rust tests not decorated by features. Our repo is configured in such a way that all such tests are ran on every PR, and failing at least one of them is blocking the PR from being pushed.

To run such tests locally run cargo test --all

- Expensive tests. This includes all the fuzzy tests that run many iterations,

as well as tests that spin up multiple nodes and run them until they reach a

certain condition. Such tests are decorated with

#[cfg(feature="expensive-tests")]. It is not trivial to enable features that are not declared in the top level crate, and thus the easiest way to run such tests is to enable all the features by passing--all-featurestocargo test, e.g:

cargo test --package near-client --test cross_shard_tx tests::test_cross_shard_tx --all-features

- Python tests. We have an infrastructure to spin up nodes, both locally and

remotely, in python, and interact with them using RPC. The infrastructure and

the tests are located in

pytestfolder. The infrastructure is relatively straightforward, see for exampleblock_production.pyhere. See theTest infrastructuresection below for details.

Expensive and python tests are not part of CI, and are run by a custom nightly runner. The results of the latest runs are available here. With today tests runs launch approximately every 5-6 hours. For the latest results look at the second run, since the first one has some tests still scheduled to run.

Test infrastructure

Different levels of the reference implementation have different infrastructure available to test them.

Client

Client is separated from the runtime via a RuntimeAdapter trait. In production

it uses NightshadeRuntime that uses real runtime and epoch managers. To test

client without instantiating runtime and epoch manager, we have a mock runtime

KeyValueRuntime.

Most of the tests in the client work by setting up either a single node (via

setup_mock()) or multiple nodes (via setup_mock_all_validators()) and then

launching the nodes and waiting for a particular message to occur, with a

predefined timeout.

For the most basic example of using this infrastructure see produce_two_blocks

in

tests/process_blocks.rs.

- The callback (

Box::new(move |msg, _ctx, _| { ...) is what is executed whenever the client sends a message. The return value of the callback is sent back to the client, which allows testing relatively complex scenarios. The tests generally expect a particular message to occur, in this case the tests expects two blocks to be produced.System::current().stop();is the way to stop the test and mark it as passed. near_network::test_utils::wait_or_panic(5000);is how the timeout for the test is set (in milliseconds).

For an example of a test that launches multiple nodes, see

chunks_produced_and_distributed_common in

tests/chunks_management.rs.

The setup_mock_all_validators function is the key piece of infrastructure here.

Runtime

Tests for Runtime are listed in tests/test_cases_runtime.rs.

To run a test, usually a mock RuntimeNode is created via

create_runtime_node(). In its constructor the Runtime is created in the

get_runtime_and_trie_from_genesis function.

Inside a test an abstraction User is used for sending specific actions to the

runtime client. The helper functions function_call, deploy_contract, etc.

eventually lead to the Runtime.apply method call.

For setting usernames during playing with transactions, use default names

alice_account, bob_account, eve_dot_alice_account, etc.

Network

TODO: explain the runner here

Chain, Epoch Manager, Runtime and other low level changes

When building new features in the chain, epoch_manager, network, make sure

to build new components sufficiently abstract so that they can be tested without

relying on other components.

For example, see tests for doomslug here, for network cache here, or for promises in runtime here.

Python tests

See this page for a detailed coverage of how to write a python test.