Zig Language Server And Cancellation

I already have a dedicated post about a hypothetical Zig language server. But perhaps the most important thing I’ve written so far on the topic is the short note at the end of Zig and Rust.

If you want to implement an LSP for a language, you need to start with a data model. If you correctly implement a store of source code which evolves over time and allows computing (initially trivial) derived data, then filling in the data until it covers the whole language is a question of incremental improvement. If, however, you don’t start with a rock-solid data model, and rush to implement language features, you might find yourself needing to make a sharp U-turn several years down the road.

I find this pretty insightful! At least, this evening I’ve been pondering a particular aspect of the data model, and I think I realized something new about the problem space! The aspect is cancellation.

Cancellation

Consider this. Your language server is happily doing something very useful and computationally-intensive — typechecking a giant typechecker, computing comptime Ackermann function, or talking to Postgres. Now, the user comes in and starts typing in the very file the server is currently processing. What is the desired behavior, and how could it be achieved?

One useful model here is strong consistency. If the language server acknowledged a source code edit, all future semantic requests (like “go to definition” or “code completion”) reflect this change. The behavior is as if all changes and requests are sequentially ordered, and the server fully processes all preceding edits before responding to a request. There are two great benefits to this model. First, for the implementor it’s an easy model to reason about. It’s always clear what the answer to a particular request should be, the model is fully deterministic. Second, the model gives maximally useful guarantees to the user, strict serializability.

So consider this sequence of events:

-

User types

fo. - The editor sends the edit to the language server.

-

The editor requests completions for

fo. - The server starts furiously typechecking modified file to compute the result.

-

User types

o. -

The editor sends the

o. -

The editor re-requests completions, now for

foo.

How does the server deal with this?

The trivial solution is to run everything sequentially to

completion. So, on the step 6, the server doesn’t

immediately acknowledge the edit, but rather blocks until it fully

completes 4. This is a suboptimal behavior, because

reads (computing completion) block writes (updating source code). As

a rule of thumb, writes should be prioritized over reads, because

they reflect more up-to-date and more useful data.

A more optimal solution is to make the whole data model of the

server immutable, such that edits do not modify data inplace, but

rather create a separate, new state. In this model, computing

results for 3 and 7 proceeds in parallel,

and, crucially, the edit 6 is accepted immediately. The

cost of this model is the requirement that all data structures are

immutable. It also is a bit wasteful — burning CPU to compute code

completion for an already old file is useless, better dedicate all

cores to the latest version.

A third approach is cancellation. On step 6, when the

server becomes aware about the pending edit, it actively cancels all

in-flight work pertaining to the old state and then applies

modification in-place. That way we don’t need to defensively copy

the data, and also avoid useless CPU work. This is the strategy

employed by rust-analyzer.

It’s useful to think about why the server can’t just, like, apply the edit in place completely ignoring any possible background work. The edit ultimately changes some memory somewhere, which might be concurrently read by the code completion thread, yielding a data race and full-on UB. It is possible to work-around this by applying feral concurrency control and just wrapping each individual bit of data in a mutex. This removes the data race, but leads to excessive synchronization, sprawling complexity and broken logical invariants (function body might change in the middle of typechecking).

Finally, there’s this final solution, or rather, idea for a solution. One interesting approach for dealing with memory which is needed now, but not in the future, is semi-space garbage collection. We divide the available memory in two equal parts, use one half as a working copy which accumulates useful objects and garbage, and then at some point switch the halves, copying the live objects (but not the garbage) over. Another place where this idea comes up is Carmack’s architecture for functional games. On every frame, a game copies over the game state applying frame update function. Because frames happen sequentially, you only need two copies of game state for this. We can think about applying something like that for cancellation — without going for full immutability, we can let cancelled analysis to work with the old half-state, while we switch to the new one.

This … is not particularly actionable, but a good set of ideas to start thinking about evolution of a state in a language server. And now for something completely different!

Relaxed Consistency

The strict consistency is a good default, and works especially well for languages with good support for separate compilation, as the amount of work a language server needs to do after an update is proportional to the size of the update, and to the amount of code on the screen, both of which are typically O(1). For Zig, whose compilation model is “start from the entry point and lazily compile everything that’s actually used”, this might be difficult to pull off. It seems that Zig naturally gravitates to a smalltalk-like image-based programming model, where the server stores fully resolved code all the time, and, if some edit triggers re-analysis of a huge chunk of code, the user just has to wait until the server catches up.

But what if we don’t do strong consistency? What if we allow IDE to temporarily return non-deterministic and wrong results? I think we can get some nice properties in exchange, if we use that semi-space idea.

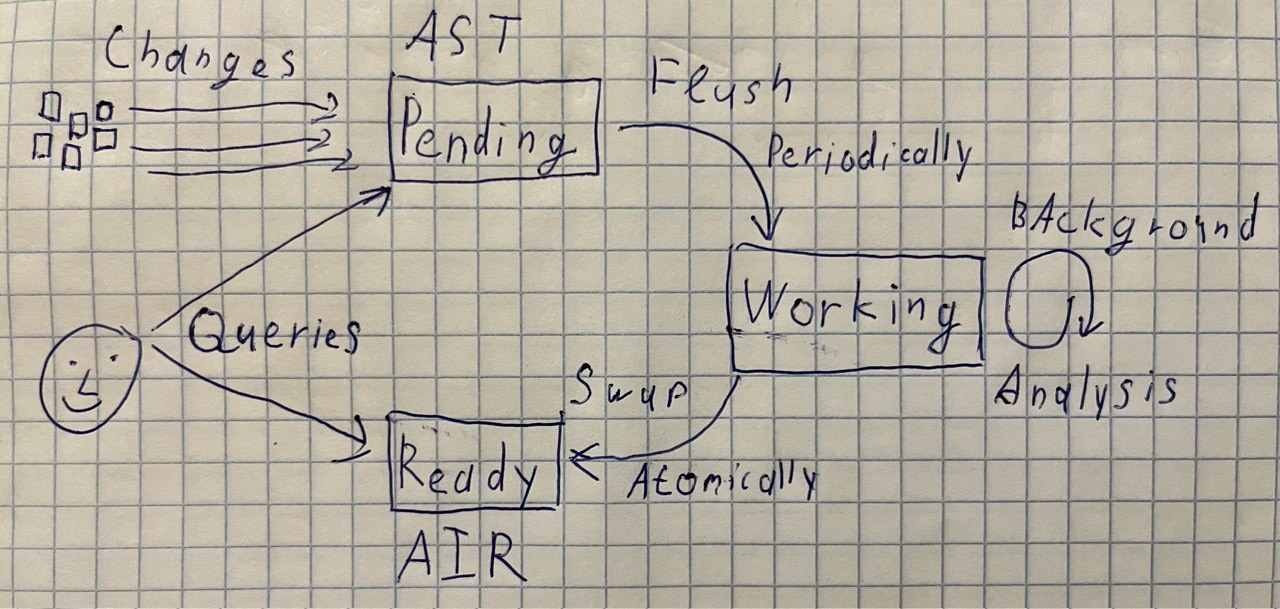

The state of our language server would be comprised of three separate pieces of data:

-

A fully analyzed snapshot of the world,

ready. This is a bunch of source file, plus their ASTs, ZIRs and AIRs. This also probably contains an index of cross-references, so that finding all usages of an identifier requires just listing already precomputed results. -

The next snapshot, which is being analyzed,

working. This is essentially the same data, but the AIR is being constructed. We need two snapshots because we want to be able to query one of them while the second one is being updated. -

Finally, we also hold ASTs for the files which are currently being

modified,

pending.

The overall evolution of data is as follows.

All edits synchronously go to the pending state.

pending is organized strictly on a per-file basis, so

updating it can be done quickly on the main thread (maaaybe we want

to move the parsing off the main thread, but my gut feeling is that

we don’t need to).

pending always reflects the latest state of the world,

it is the latest state of the world.

Periodically, we collect a batch of changes from pending, create a new working and kick off a

full analysis in background. A good point to do that would be when

there’s no syntax errors, or when the user saves a file. There’s at

most one analysis in progress, so we accumulate changes in pending until the previous analysis finishes.

When working is fully processed, we atomically update

the ready. As ready is just an inert piece

of data, it can be safely accessed from whatever thread.

When processing requests, we only use ready and pending. Processing requires some heuristics.

ready and pending describe different

states of the world.

pending guarantees that its state is up-to-date, but it

only has AST-level data.

ready is outdated, but it has every bit of

semantic information pre-computed. In particular, it includes

cross-reference data.

So, our choices for computing results are:

-

Use the

pendingAST. Features like displaying the outline of the current file or globally fuzzy-searching function by name can be implemented like this. These features always give correct results. -

Find the match between the

pendingAST and thereadysemantics. This works perfectly for non-local “goto definition”. Here, we can temporarily get “wrong” results, or no result at all. However, the results we get are always instant. -

Re-analyze

pendingAST using results fromreadyfor the analysis of the context. This is what we’ll use for code completion. For code completion,pendingwill be maximally diverging fromready(especially if we use “no syntax errors” as a heuristic for promotingpendingtoworking), so we won’t be able to complete based purely onready. At the same time, completion is heavily semantics-dependent, so we won’t be able to drive it throughpending. And we also can’t launch full semantic analysis onpending(what we effectively do inrust-analyzer), due to “from root” analysis nature.But we can merge two analysis techniques. For example, if we are completing in a function which starts as

fn f(comptime T: type, param: T), we can usereadyto get a set of values ofTthe function is actually called with, to completeparam.in a useful way. Dually, if insidefwe have something likeconst list = std.ArrayList(u32){}, we don’t have tocomptimeevaluate theArrayListfunction, we can fetch the result fromready.Of course, we must also handle the case where there’s no

readyyet (it’s a first compilation, or we switched branches), so completion would be somewhat non-deterministic.

One important flow where non-determinism would get in a way is

refactoring. When you rename something, you should be 100% sure that

you’ve found all usages. So, any refactor would have to be a

blocking operation where we first wait for the current working to complete, then update working with

the pending accumulated so far, and wait for that to complete, to, finally, apply the refactor using only

up-to-date ready. Luckily, refactoring is almost always

a two-phase flow, reminiscent of a GET/POST flow for HTTP form (more about that). Any refactor starts with read-only analysis

to inform the user about available options and to gather input. For

“rename”, you wait for the user to type the new name, for “change

signature” the user needs to rearrange params. This brief

interactive window should give enough headroom to flush all pending changes, masking the latency.

I am pretty excited about this setup. I think that’s the way to go for Zig.

- The approach meshes extremely well with the ambition of doing incremental binary patching, both because it leans on complete global analysis, and because it contains an explicit notion of switching from one snapshot to the next one (in contrast, rust-analyzer never really thinks about “previous” state of the code. There’s always only the “current” state, with lazy, partially complete analysis).

- Zig lacks declared interfaces, so a quick “find all calls to this function” operation is required for useful completion. Fully resolved historical snapshot gives us just that.

-

Zig is carefully designed to make a lot of semantic information

obvious just from the syntax. Unlike Rust, Zig lacks syntactic

macros or glob imports. This makes is possible to do a lot of

analysis correctly using only

pendingASTs. - This approach nicely dodges the cancellation problem I’ve spend half of the blog post explaining, and has a relatively simple threading story, which reduces implementation complexity.

- Finally, it feels like it should be super fast (if not the most CPU efficient).

Discussion on /r/Zig.