An Engine for an Editor

A common trope is how, if one wants to build a game, one should build a game, rather than a game engine, because it is all too easy to fall into a trap of building a generic solution, without getting to the game proper. It seems to me that the situation with code editors is the opposite — many people build editors, but few are building “editor engines”. What’s an “editor engine”? A made up term I use to denote a thin waist the editor is build upon, the set of core concepts, entities and APIs which power the variety of editor’s components. In this post, I will highlight Emacs’ thin waist, which I think is worthy of imitation!

Before we get to Emacs, lets survey various APIs for building interactive programs.

- Plain text

-

The simplest possible thing, the UNIX way of programs-filters, reading input from stdin and writing data to stdout. The language here is just plain text.

- ANSI escape sequences

-

Adding escape codes to plain text (and a bunch of

ioctls) allows changing colors and clearing the screen. The language becomes a sequence of commands for the terminal (with “print text” being a fairly frequent one). This already is rich enough to power a variety of terminal applications, such as vim! - HTML

-

With more structure, we can disentangle ourselves from text, and say that all the stuff is made of trees of attributed elements (whose content might be text). That turns out to be enough to express basically whatever, as the world of modern web apps testifies.

- Canvas

-

Finally, to achieve maximal flexibility, we can start with a clean 2d canvas with pixels and an event stream, and let the app draw however it likes. Desktop GUIs usually work that way (using some particular widget library to encapsulate common patterns of presentation and event handling).

Emacs is different. Its thin waist consists of (using idiosyncratic olden editor terminology) frames, windows, buffers and attributed text. This is less general than canvas or HTML, but more general (and way more principled) than ANSI escapes. Crucially, this also retains most of plain text’s composability.

The foundation is a text with attributes — a pair of a string and a map from string’s subranges to key-value dictionaries. Attributes express presentation (color, font, text decoration), but also semantics. A range of text can be designated as clickable. Or it can specify a custom keymap, which is only active when the cursor is on this range.

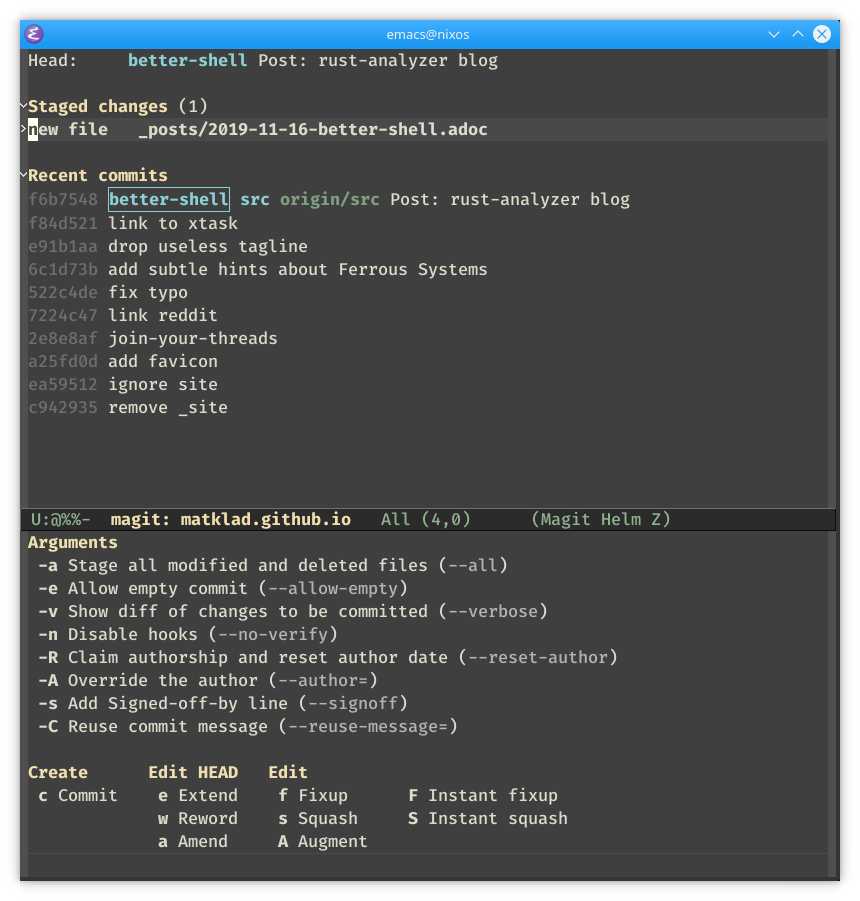

I find this to be a sweet spot for building efficient user interfaces. Consider magit:

The interface is built from text, but it is more discoverable, more readable, and more efficient than GUI solutions.

Text is surprisingly good at communicating with humans! Forgoing arbitrary widgets and restricting oneself to a grid of characters greatly constrains the set of possible designs, but designs which come out of these constraints tend to be better.

The rest (buffers, windows, and frames) serve to present attributed strings to the user. A Buffer holds a piece of text and stores position of the cursor (and the rest of editor’s state for this particular piece of text). A tiling window manager displays buffers:

- there’s a set of floating windows (frames in Emacs terminology) managed by a desktop environment

- each floating window is subdivided into a tree of vertical and horizontal splits (windows) managed by Emacs

- each split displays a buffer, although some buffers might not have a corresponding split

There’s also a tasteful selection of extras outside this orthogonal model. A buffer holds a status bar at the bottom and a set of fringe decorations at the left edge. Each floating window has a minibuffer — an area to type commands into (minibuffer is a buffer though — only presentation is slightly unusual).

But the vast majority of everything else is not special — every

significant thing is a buffer. So, ./main.rs file, ./src file tree, a terminal session where you type cargo

build are all displayed as attributed text. All use the same

tools for navigation and manipulation.

Universality is the power of the model. Good old UNIX pipes, except interactive. With a GUI file manager, mass-renaming files requires a dedicated utility. In Emacs, file manager’s state is text, so you can use standard text-manipulation tools (regexes, multiple cursors, vim’s .) for the same task.

Conclusions

Pay more attention to the editor’s thin waist. Don’t take it as a given that an editor should be a terminal, HTML, or GUI app — there might be a better vocabulary. In particular, Emacs seems to hit the sweet spot with its language of attributed strings and buffers.

I am not sure that Emacs is the best we can do, but having a Rust library which implements Emacs model more or less as is would be nice! The two best resources to learn about this model are

-

this diagram:

https://www2.lib.uchicago.edu/keith/emacs/#org9c6cafa -

this section of Emacs docs:

https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/manual/html_node/elisp/Text-Properties.html