Spinlocks Considered Harmful

Happy new year 🎉!

In this post, I will be expressing strong opinions about a topic I have relatively little practical experience with, so feel free to roast and educate me in comments (link at the end of the post) :-)

Specifically, I’ll talk about:

- spinlocks,

-

spinlocks in Rust with

#[no_std], - priority inversion,

- CPU interrupts,

- and a couple of neat/horrible systemsy Rust hacks.

Context

I maintain once_cell crate, which is a synchronization primitive.

It uses std blocking facilities under the hood

(specifically, std::thread::park), and as such is not

compatible with #[no_std]. A popular request is to add

a spin-lock based implementation for use in #[no_std]

environments: #61.

More generally, this seems to be a common pattern in Rust ecosystem:

-

A crate uses

Mutexor other synchronization mechanism fromstd -

Someone asks for

#[no_std]support -

Mutexis swapped for some variation of spinlock.

For example, the lazy_static crate does this:

github.com/rust-lang-nursery/lazy-static.rs/blob/master/src/core_lazy.rs

I think this is an anti-pattern, and I am writing this blog post to call it out.

What Is a Spinlock, Anyway?

A Spinlock is the simplest possible implementation of a

mutex, its general form looks like this:

static LOCKED: AtomicBool = AtomicBool::new(false);

while LOCKED.compare_and_swap(false, true, Ordering::Acquire) {

std::sync::atomic::spin_loop_hint();

}

/* Critical section */

LOCKED.store(false, Ordering::Release);

- To grab a lock, we repeatedly execute compareandswap until it succeeds. The CPU “spins” in this very short loop.

- Only one thread at a time can be here.

- To release the lock, we do a single atomic store.

- Spinning is wasteful, so we use an intrinsic to instruct the CPU to enter a low-power mode.

Why we need Ordering::Acquire and Ordering::Release is very interesting, but beyond the scope

of this article.

The key take-away here is that a spinlock is implemented entirely in user space: from OS point of view, a “spinning” thread looks exactly like a thread that does a heavy computation.

An OS-based mutex, like std::sync::Mutex or parking_lot::Mutex, uses a system

call to tell the operating system that a

thread needs to be blocked. In pseudo code, an implementation might

look like this:

static LOCKED: AtomicBool = AtomicBool::new(false);

while LOCKED.compare_and_swap(false, true, Ordering::Acquire)

park_this_thread(&LOCKED);

}

/* Critical section */

LOCKED.store(false, Ordering::Release);

unpark_some_thread(&LOCKED);

The main difference is park_this_thread — a blocking system call. It instructs the OS

to take current thread off the CPU until it is woken up by an unpark_some_thread call. The kernel maintains a queue of threads waiting for a mutex. The park call enqueues current thread onto this queue, while

unpark dequeues some thread. The park

system call returns when the thread is dequeued. In the meantime,

the thread waits off the CPU.

If there are several different mutexes, the kernel needs to maintain several queues. An address of a lock can be used as a token to identify a specific queue (this is a futex API).

System calls are expensive, so production implementations of Mutex usually spin for several iterations before calling

into OS, optimistically hoping that the Mutex will be

released soon. However, the waiting always bottoms out in a syscall.

Spinning Just For a Little Bit, What Can Go Wrong?

Because spin locks are so simple and fast, it seems to be a good idea to use them for short-lived critical sections. For example, if you only need to increment a couple of integers, should you really bother with complicated syscalls? In the worst case, the other thread will spin just for a couple of iterations…

Unfortunately, this logic is flawed! A thread can be preempted at any time, including during a short critical section. If it is preempted, that means that all other threads will need to spin until the original thread gets its share of CPU again. And, because a spinning thread looks like a good, busy thread to the OS, the other threads will spin until they exhaust their quants, preventing the unlucky thread from getting back on the processor!

If this sounds like a series of unfortunate events, don’t worry, it gets even worse. Enter Priority Inversion. Suppose our threads have priorities, and OS tries to schedule high-priority threads over low-priority ones.

Now, what happens if the thread that enters a critical section is a low-priority one, but competing threads have high priority? It will likely get preempted: there are higher priority threads after all. And, if the number of cores is smaller than the number of high priority threads that try to lock a mutex, it likely won’t be able to complete a critical section at all: OS will be repeatedly scheduling all the other threads!

No OS, no problem?

But wait! — you would say — we only use spin locks in #[no_std] crates, so there’s no OS to preempt our threads.

First, it’s not really true: it’s perfectly fine, and often

even desirable, to use #[no_std] crates for usual

user-space applications. For example, if you write a Rust

replacement for a low-level C library, like zlib or openssl, you

will probably make the crate #[no_std], so that

non-Rust applications can link to it without pulling the whole of

the Rust runtime.

Second, if there’s really no OS to speak about, and you are on the bare metal (or in the kernel), it gets even worse than priority inversion.

On bare metal, we generally don’t worry about thread preemption, but we need to worry about processor interrupts. That is, while processor is executing some code, it might receive an interrupt from some periphery device, and temporary switch to the interrupt handler’s code.

And here comes the disaster: if the main code is in the middle of the critical section when the interrupt arrives, and if the interrupt handler tries to enter the critical section as well, we get a guaranteed deadlock! There’s no OS to switch threads after a quant expires. Here are Linux kernel docs discussing this issue.

Practical Applications

Let’s trigger priority inversion! Our victim is the getrandom crate. I don’t pick on getrandom specifically here: the pattern is pervasive across

the ecosystem.

The crate uses spinning in the LazyUsize utility type:

pub struct LazyUsize(AtomicUsize);

impl LazyUsize {

// Synchronously runs the init() function. Only one caller

// will have their init() function running at a time, and

// exactly one successful call will be run. init() returning

// UNINIT or ACTIVE will be considered a failure, and future

// calls to sync_init will rerun their init() function.

pub fn sync_init(

&self,

init: impl FnOnce() -> usize,

mut wait: impl FnMut(),

) -> usize {

// Common and fast path with no contention.

// Don't wast time on CAS.

match self.0.load(Relaxed) {

Self::UNINIT | Self::ACTIVE => {}

val => return val,

}

// Relaxed ordering is fine,

// as we only have a single atomic variable.

loop {

match self.0.compare_and_swap(

Self::UNINIT,

Self::ACTIVE,

Relaxed,

) {

Self::UNINIT => {

let val = init();

self.0.store(

match val {

Self::UNINIT | Self::ACTIVE => Self::UNINIT,

val => val,

},

Relaxed,

);

return val;

}

Self::ACTIVE => wait(),

val => return val,

}

}

}

}

There’s a static instance of LazyUsize

which caches file descriptor for /dev/random:

https://github.com/rust-random/getrandom/blob/v0.1.13/src/use_file.rs#L26

This descriptor is used when calling getrandom — the

only function that is exported by the crate.

To trigger priority inversion, we will create 1 + N

threads, each of which will call getrandom::getrandom.

We arrange it so that the first thread has a low priority, and the

rest are high priority. We stagger threads a little bit so that the

first one does the initialization. We also make creating the file

descriptor slow, so that the first thread gets preempted while in

the critical section.

Here is the implementation of this plan: https://github.com/matklad/spin-of-death.

It uses a couple of systems programming hacks to make this disaster

scenario easy to reproduce. To simulate slow /dev/random, we want to intercept the poll

syscall getrandom is using to ensure that there’s

enough entropy. We can use strace

to log system calls issued by a program. I don’t know if strace can

be used to make a syscall run slow (now, once I’ve looked at the

website, I see that it can in fact be used to tamper with syscalls,

sigh), but we actually don’t need to!

getrandom does not use the syscall directly, it uses

the poll function from libc. We can

substitute this function by using LD_PRELOAD, but

there’s an even simpler way! We can trick the static linker into

using a function which we define ourselves:

pub extern "C" fn poll(

_fds: *const u8,

_nfds: usize,

_timeout: i32,

) -> u32 {

sleep_ms(500);

1

}

The name of the function accidentally ( :) ) clashes with a well-known POSIX function.

However, this alone is not enough.

getrandom tries to use getrandom syscall first, and that

code path does not use a spin lock. We need to fool getrandom into believing that the syscall is not available.

Our extern "C" trick wouldn’t have worked if getrandom literally used the syscall

instruction. However, as inline assembly (which you need to issue a

syscall manually) is not available on stable Rust, getrandom goes via syscall function

from libc. That we can override with the same trick.

However, there’s a wrinkle! Traditionally, libc API

used errno for error reporting. That is, on a failure

the function would return an single specific invalid value, and set

the errno thread local variable to the specific error

code. syscall follows this pattern.

The errno interface is cumbersome to use. The worst

part of errno is that the specification requires it to

be a macro, and so you can only really use it from C

source code. Internally, on Linux the macro calls __get_errno_location function to get the thread local, but

this is an implementation detail (which we will gladly take

advantage of, in this land of reckless systems hacking!). The irony

is that the ABI of Linux syscall just returns error

codes, so libc has to do some legwork to adapt to the

awkward errno interface.

So, here’s a strong contender for the most cursed function I’ve written so far:

pub extern "C" fn syscall(

_syscall: u64,

_buf: *const u8,

_len: usize,

_flags: u32,

) -> isize {

extern "C" {

fn __errno_location() -> *mut i32;

}

unsafe {

*__errno_location() = 38; // ENOSYS

}

-1

}

It makes getrandom believe that there’s no getrandom syscall, which causes it to fallback to /dev/random implementation.

To set thread priorities, we use thread_priority crate, which is a thin wrapper around pthread APIs. We will be using real time priorities, which

require sudo.

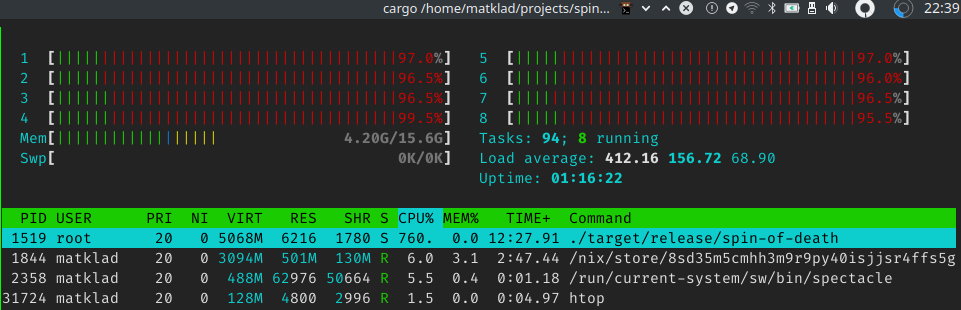

And here are the results:

$ cargo build --release

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.01s

$ time sudo ./target/release/spin-of-death

^CCommand terminated by signal 2

real 136.54s

user 96.02s

sys 940.70s

rss 6880k

Note that I had to kill the program after two minutes. Also note the impressive system time, as well as load average

If we patch getrandom to use std::sync::Once instead we get a much better result:

$ cargo build --release --features os-blocking-getrandom

Finished release [optimized] target(s) in 0.01s

$ time sudo ./target/release/spin-of-death

real 0.51s

user 0.01s

sys 0.04s

rss 6912k

-

Note how

realis half a second, butuserandsysare small. That’s because we are waiting for 500 milliseconds in ourpoll

This is because Once uses OS facilities for blocking,

and so OS notices that high priority threads are actually blocked

and gives the low priority thread a chance to finish its work.

If Not a Spinlock, Then What?

First, if you only use a spin lock because “it’s faster for

small critical sections”, just replace it with a mutex from std or parking_lot. They already do a small

amount of spinning iterations before calling into the kernel, so

they are as fast as a spinlock in the best case, and infinitely

faster in the worst case.

Second, it seems like most problematic uses of spinlocks

come from one time initialization (which is exactly what my once_cell crate helps with). I think it usually is possible

to get away without using spinlocks. For example, instead of storing

the state itself, the library may just delegate state storing to the

user. For getrandom, it can expose two functions:

fn init() -> Result<RandomState>;

fn getrandom(state: &RandomState, buf: &mut[u8]) -> Result<usize>;

It then becomes the user’s problem to cache RandomState

appropriately. For example, std may continue using a thread local

(src) while rand, with std feature enabled, could

use a global variable, protected by Once.

Another option, if the state fits into usize and the

initializing function is idempotent and relatively quick, is to do a

racy initialization:

pub fn get_state() -> usize {

static CACHE: AtomicUsize = AtomicUsize::new(0);

let mut res = CACHE.load(Ordering::Relaxed);

if res == 0 {

res = init();

CACHE.store(res, Ordering::Relaxed);

}

res

}

fn init() -> usize { ... }

Take a second to appreciate the absence of unsafe

blocks and cross-core communication in the above example!

At worst, (EDIT: this is wrong, thanks to

/u/pcpthm for pointing this out!).

init will be called number of

cores times

There’s also a nuclear option: parametrize the library by blocking behavior, and allow the user to supply their own synchronization primitive.

Third, sometimes you just know that there’s only a single thread in the

program, and you might want to use a spinlock just to silence those

annoying compiler errors about static mut. The primary

use case here I think is WASM. A solution for this case is to assume

that blocking just doesn’t happen, and panic otherwise. This is what

std does for Mutex on WASM, and what is

implemented for once_cell in this PR: #82.

Discussion on /r/rust.

EDIT: If you enjoyed this post, you might also like this one:

Looks like we have some contention here!

EDIT: there’s now a follow up post, where we actually benchmark spinlocks:

https://matklad.github.io/2020/01/04/mutexes-are-faster-than-spinlocks.html